Temples and Services

The Immaculate house of worship is called the temple. Where the family shrine is the focus of spirituality for the individual, the temple is the focus of spirituality for the community. Temples serve not only as places to hold ceremonies and lectures, but also as centers for community activity.

Immaculate faithful are called to attend temples regularly and frequently. The temple is the beating heart of the local Immaculate community, and the main place in which the faithful are able to interact formally with the monks. Monks often leave the temple grounds to invest themselves in the community, so it is not the only place to encounter them, but all threads of faith lead back to the temple.

Monks are the formal clergy of the Immaculate Order, those who have given up their material life in order to pursue a spiritual one. For many Immaculates, the presence of monks is ubiquitous. If a temple is nearby, then there are monks there, who offer frequent wisdom, insight, and suggestions for moral life. Even in the most remote villages, monks sometimes come to visit, bringing wisdom and advice.

The Order is devoted to ensuring that every devout Immaculate, no matter their far-flung location, has access, even if only occasionally, to the wisdom of the Order and guidance on their spiritual affairs. All monks are empowered to make decisions based on the Texts and offer advice on personal affairs. When a community loses a monk to death or her retirement to a monastery, there is great sadness, for the community has not only lost a leader, but also a close friend and confidant – sometimes of many generations.

Immaculate Temples

Immaculate temples are designed in accordance with principles of sacred geometry and geomancy. They are laid out in a shape that concentrates positive energy at the focal point, where the innermost sanctum is arranged. Symmetry is a major focus of the temple, representing harmony and stability.

Very small temples, such as the consecrated household shrines found on many Dynastic compounds, are not bound by these designs, and usually consist only of what would be the central building in a larger temple. Monks out in the world are sometimes called upon for use of a temple when none is available; in these cases, they can construct an on-the-fly sanctified temple by simply drawing a square in the dirt and inscribing a circle within it.

Parts of a Temple

The temple is composed of two subdivisions: the outer temple and the inner temple. The design of the inner temple is fairly standardized and fixed, while the design of the outer temple can vary wildly.

The Inner Temple

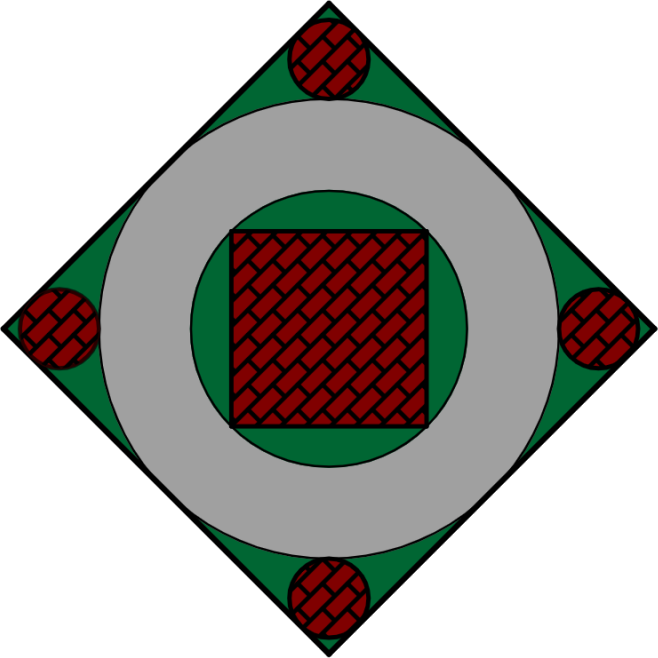

The inner temple is a standardized layout based on Pasiap’s Sacred Geometry: the circle inscribed within the square. In this mystical plan, the square represents Creation, and the interior circle represents the sacred temple space. The square, which is usually the outer wall, is always aligned so that the four corners each point in a cardinal direction.

A typical inner temple is designed with a large circular ambulatory, surrounding a central interior circle. This circle houses a square building, arranged with corners facing the centers of the sides of the outer wall; each face thus points in a cardinal direction, with a wide window looking out over the shrine in that corner.

Each corner of the inner temple is home to a shrine representing one of the Immaculate Dragons: Mela to the north, Sextes Jylis to the east, Hesiesh to the south, and Daana’d to the west. The shrine to Pasiap is housed within the central building. Thus, every temple has five major shrines housed within the inner temple.

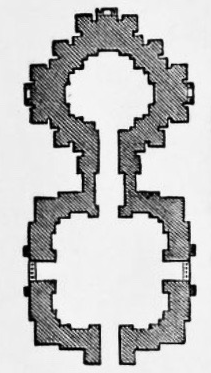

The four directional shrines are often very grand, and usually free-standing buildings surrounded by gardens within their wedge. In small temples, these shrines may be housed within gazebos, but sprawling temples will construct entire buildings. One popular shape is Pasiap’s Cudgel:

The cudgel features a large entry room for meditation and reflection, and an elevated interior room where the shrine itself is housed.

The shapes of the buildings within the inner temple is variable, as long as it remains symmetrical. Some larger temples enclose the inner temple entirely, with arcing glass allowing sunlight into the ambulatory; most temples, however, leave the inner temple exposed to the air.

The Outer Temple

The outer temple is all parts of the temple that surround the walls of the inner temple. For small temples, there may be very little of the outer temple, simply a manicured ground and some buildings for the monks to live inside of. In large temples, the outer temple may have another set of walls or even two, and the space can be home to dozens of buildings, spectacular gardens, and towering minarets.

Monks make their homes within the outer temple, as well as carry out most of their non-faithful business here. The outer temple usually features public buildings like schoolrooms, meditation halls, and clinics. The outer temple is meant to be extremely accessible to the community, to provide a place in which the community can gather and interact with their spiritual leaders.

It is traditional, even in sparsely-populated areas, to feature a special gate, the “Rainbow Gate”, which is only permitted to be used by the Dragon-Blooded. The Rainbow Gate features a direct path to the inner temple via the “Stormcloud Gate”; this allows the Princes of the Earth to go about their business unimpeded. In many temples, the rainbow gate and stormcloud gate are the most intricately decorated gates in the facility.

Uses of the Temple

In addition to providing a sacred space for formal services, the temple is also a meeting place and hub of the community. Monks encourage frequent visits to the temple, and all holidays and celebrations are held within the temple.

The temple watches over all stages of life and has ceremonies for all occasions. Throughout the Blessed Isle, children are not named until they are brought to the temple and have their name recited by a monk in a naming ceremony – until that point, they are simply “boy” or “girl.” Marriages are usually performed at the local temple, as well as celebrations of birth and mourning of the dead. The temple is home to the local House of the Dead, usually in the outer temple or outside the temple entirely and accessed by a path, which houses the cremated remains of the dead and serves as a place of remembrance for the deceased.

The monks at the temple are responsible for basic education, so the temple often has chambers set aside for schooling and childcare. The monks are often the most qualified people to act as physicians, so many temples include a House of the Ailing where the monks can tend to the wounded, offer herbal treatments, and ease suffering.

Monks are outside of politics and expert maintainers of old texts, so local governments often shelter their records within the local temple. Sometimes local workers even trust the temple to handle the accounting of loans, leaving valuable collateral to the temple, where it is secured within the walls and will not be absconded with during the process of settlement.

In conclusion, the temple provides for all aspects of life. The local temple is often a vital organ of local public life, a place where all ranks of the community come and go. The monks serve as a social glue that spans boundaries of class and status, an impartial outside force that offers wisdom and guidance.

Services

Immaculate services are focused primarily on chanting, meditation, and group involvement. The goal of a service is to instill moral lessons that can be applied to daily life and to guide the faithful toward accumulating merit by filling their station.

Temples host regularly-scheduled services throughout the week, and larger temples throughout the day. Monks encourage the community to attend as many services as they are able, in order to interact with other members of the community and receive regular guidance on their lives.

Immaculate services are lead by the monks in the central building of the inner temple, with space reserved at the front for the Dragon-Blooded and mortals in the rest of the space. In small temples that know they are unlikely to receive attendance by living saints, the place of honor is usually small and ceremonial.

A Typical Service

A typical service in the Rainbow Gate of Wisdom lineage follows a predictable pattern. Once the crowd is assembled, a bell is rung or drum is beat to call the service to begin. The assembled stand while the presiding monks take their place at the front of the assembly. They lead the crowd in several chants, and then five prostrations toward each of the five shrines of the inner temple.

Following prostrations, the monks gather the crowd to be seated, and the presiding monk takes her place at the front of the assembly on a raised platform. The monks make their way among the assembled, offering water from a sacred vessel with which to wash the hands and face. Once the water has been distributed, the presiding monk begins a recitation of the day’s sutras. In most temples, the monk reads from an oversized copy of the Immaculate Texts, with pages several feet across, placed on sacred blankets. Normally, only the page currently being read is exposed; the other page is covered by a blanket until it is read.

All Immaculate chants and recitations are set to music. Monks assembled at the rear of the temple play drums, flutes, and other instruments to set the tone of the ceremony. This allows those in attendance to hum, clap, or vocalize along with the recitation, even if they do not know the words.

Following the recitation, the monks lead the congregation in making offerings to each of the Five Elemental Dragons. These offerings are carried among the congregation, every attendant bowing before the offering as it passes, and then placed at the window corresponding to each of the shrines. Mela is always first, offered perfumes, feathers, sweet-scented oils, a fan, a lantern, etc. Then Sextes Jylis, offered flowers, leafy branches, fresh fruit and vegetables, etc.; Hesiesh, offered burning incense, bells, pots of tea, etc.; and Daana’d, offered sacred water, seashells, a mirror, seaweed, etc. Lastly, the monks offer bread, coins, salt, and milk to Pasiap at the center. The exact offerings for the day vary, and are determined based on complicated schedules within the sacred manuals. During all of this, the crowd chants for transformation of the mundane into the divine and gratitude for the teachings of the Immaculate Dragons.

After offerings are made, the presiding monk offers a homily on the recitation for the day. This homily is up to the presiding monk, so it can be rambling and detailed or short and concise depending on the monk. The homily is intended for the community at large; individual practitioners can seek private sessions with the monks to discuss their specific situation, and its solutions based on the Texts, in more detail.

The final phase of the service is the worship of the gods prescribed for that day by the local calendar. The monks lead the crowd to the exterior shrine in the outer temple, which is reserved for this function. There, they assemble an offering tray appropriate to the god being revered, and lead the congregation in many rote prayers personalized for the deity being revered. After the prayers are said, the monks specify which good should be offered at home the next day as part of the worship. The service is then complete.

Special Services

Special services take place for atypical circumstances like funerals, namings, marriages, and so forth. The exact form that these special services take depends on the local tradition and the circumstances of the event. Most of these special celebrations take place in the outer temple, at a place of importance.

Namegiving ceremonies bestow a formal name onto the child, and are joyous celebrations for the whole community. Namegivings are typically held one year and one day after the child is born; until that point, the child is nameless, which helps keep malicious spirits from stealing them away. By the time the namegiving comes around, the monks have already consulted with the parents and helped to choose an auspicious name. There is a great big celebration with music and dancing and food, and the baby is named after a monk whispers the baby’s name in each ear five times, covering the other ear with a flower, fan, smooth stone, mirror, or bell, depending on the child’s protective element. Then, the child is introduced to the Dragons by taking them to the inner temple for the first time and touring the five shrines and reciting protective chants.

Marriages are highly dependent on local tradition, but are usually orchestrated by a monk. Most marriages involve tying two cords around the entwined hands of the participants; the cords are a braid of five twines colored for the elements, and represents the ties that bond the couple in marriage. Once the cording is complete, the spouses wear the cords as necklaces for five days.

Funerals are usually private affairs, and involve making a final chant over the body and a vigil held by the family at the temple. During the vigil, mourners can come by to chant over the deceased or seek counsel from the monks. Once the vigil is complete, the body is disposed of. Most funerals end in cremation on a pyre; devotees of a specific Dragon may choose an alternative. Some devotees of Pasiap are mummified; the costs of mummifying and maintaining a mummified tomb fall to the family, so this is rather rare. Devotees of Daana’d are buried at sea or sunk into lakes. Devotees of Sextes Jylis are buried and have trees or flowers planted over their corpse. Lastly, rarest of all, some devotees of Mela opt for a sky burial, allowing their bodies to be picked clean by birds in special towers far from settlements.

Physical Attendance of Gods

The Immaculate Philosophy is practiced not only by humans, but also by spirits of many kinds who have been converted. Such gods and spirits are not denied access to the temple, and are permitted to chant, meditate, and pray like any other practitioner during service – but are handled with extra care.

Gods who choose to attend service are kept segregated from mortal practitioners for the sake of the souls of both. Spirits are pushed to the far left and far right of the mortal practitioners, and separated physically; they are expected to move as the crowd moves, unlike mortal practitioners who can rotate in place when the direction of worship changes. This ensures that worship is never directed at the spirits. Larger temples, or temples with regular attendance by spirits, have balcony platforms reserved for spirits in attendance, which allow them a greater degree of freedom of movement than being on the floor with mortals.

Gods and spirits are also allowed personal religious guidance just like mortals, and can request assistance on matters of faith from the monks. Pastoral care of gods and spirits is a complicated and messy affair with lots of detailed and nuanced questions, so it is usually performed by ranking monks. In the same way as mortals come to cherish their monks, gods and spirits also often come to view the elder monks at their local temple as friends – in turn, these pious gods tend to be easier to deal with, which creates a reinforcing cycle of amicable understanding in the best circumstances.

Gods At Their Own Worship

Sometimes, gods like to attend their own days of worship in person to observe or take part in the service. The monks have a special procedure for these days.

The presiding monk will always be an elder, and wears special robes to reflect the circumstance. The service has a greater emphasis on text readings and the homily usually involves a lecture on the proper relationship between mortals and gods. If at all possible, a Prince of the Earth is made to attend, or – ideally – to preside, if the temple is lucky enough to merit a Prince among its monks.

The presiding monk leads the congregation to the worship shrine as usual, but carries with her a coiled whip (ideally for a Prince, a sacred direlash held by the temple) and a sword. The monk whips at the air and beckons the god to come forth. The presiding monk recites a catechism with the god outlining the position of gods and their relationship to mortals. Then, the god offers the sword to the monk, who accepts it and allows the god to enter their shrine.

Having prepared and contextualized the act of worship, the assembly is now permitted to directly worship the god in attendance, under the strict supervision of the monks. This direct, physical worship is highly desireable by gods and spirits, who bear the humiliation of the ritual for the high of worship in person.